Park Number: 55/63

First Visited: May 15, 2019

The park in question is a 630-foot arch. In terms of geology, this measurement would be record setting, more than doubling the world’s next closest arch in both height and span, if the thing was natural, but it’s not. This arch is human built, constructed between 1963 and 1965, and, according to its funding advocates, to be “a memorial to the men who made possible the western territorial expansion of the United States.” Stainless steel covers the structure and glistens to city lights, with corporate logos like “Shipworks” and “Hyatt” owning the immediate skyline. Interstate 44 runs beneath the 91-acre park property, offering the bustle and air pollution of a 2.9-million-person population skittering hither and yon. No night sky. No silence. Just a city predicated upon industrial progress and its consequences—

What we have is downtown St. Louis, Missouri, and its freshly designated “Gateway Arch National Park.”

To understand the significance of this outcome first requires a minor understanding of the National Park Services’ tangled history of development, establishment, and expansion. During the last 150 years, via political jostling over public lands management, the NPS has come to administrate 419 park units. These units can range from designations like national lakeshores to national monuments to national historic trails. By my estimation there are over 40 different designations, though many are so close in nomenclature it’s hard to justify distinction: like a national historic site vs. a national historic park vs. a national historical park, or a national battlefield vs. a national battlefield park vs. a national battlefield site. Of this list, the apex has long been the full-fledged national park. These would be your Yellowstones, Yosemites, and Grand Canyons. Of the 419 units, 62 are national parks. Gateway Arch, formally designated as a national memorial, is now included in this elite group.

The designation upgrade came on February 22, 2018, when President Trump signed into law S. 1438, the “Gateway Arch National Park Designation Act,” setting in motion the rebranding of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. Trump’s signature came on the heels of congressional approval, which faced little opposition and moved through the House and Senate within eight months (for context, it took over a decade for Grand Teton to get approval). Senator Roy Blunt, one of the Gateway legislation’s Republican sponsors, explained that, “renaming the park will better highlight its central feature and make it more immediately recognizable to the millions of people who visit St. Louis every year.” Further research gives similar reasonings: it was a bi-partisan move, in a bi-partisan state, during a time of little compromise and cooperation in Congress, that united both parties under a mutual interest. Rebranding the “memorial” as a “national park” was sure to re-stimulate Missouri’s stagnant economy and draw tourists in through the trusted outdoor trademark. And it worked.

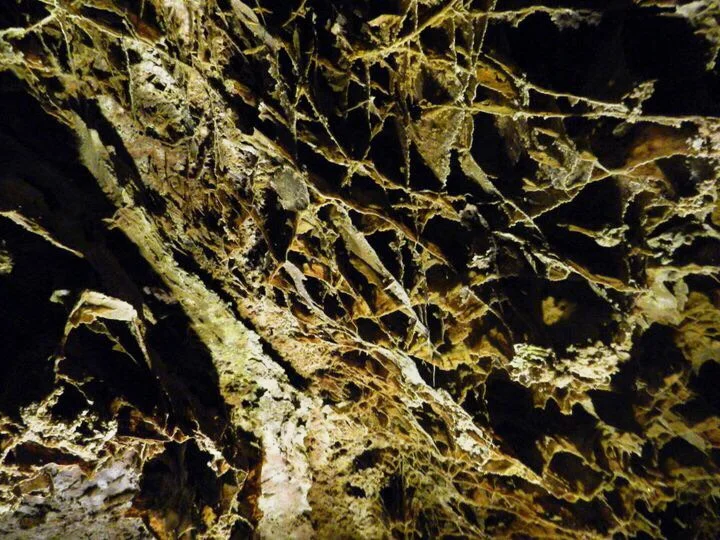

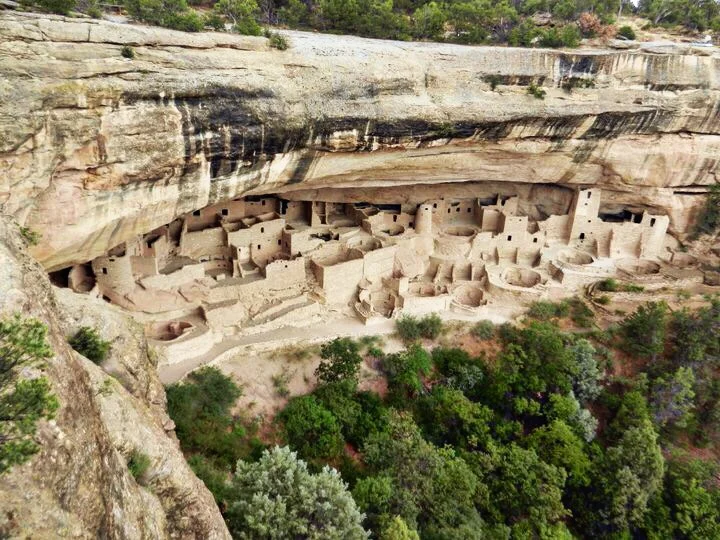

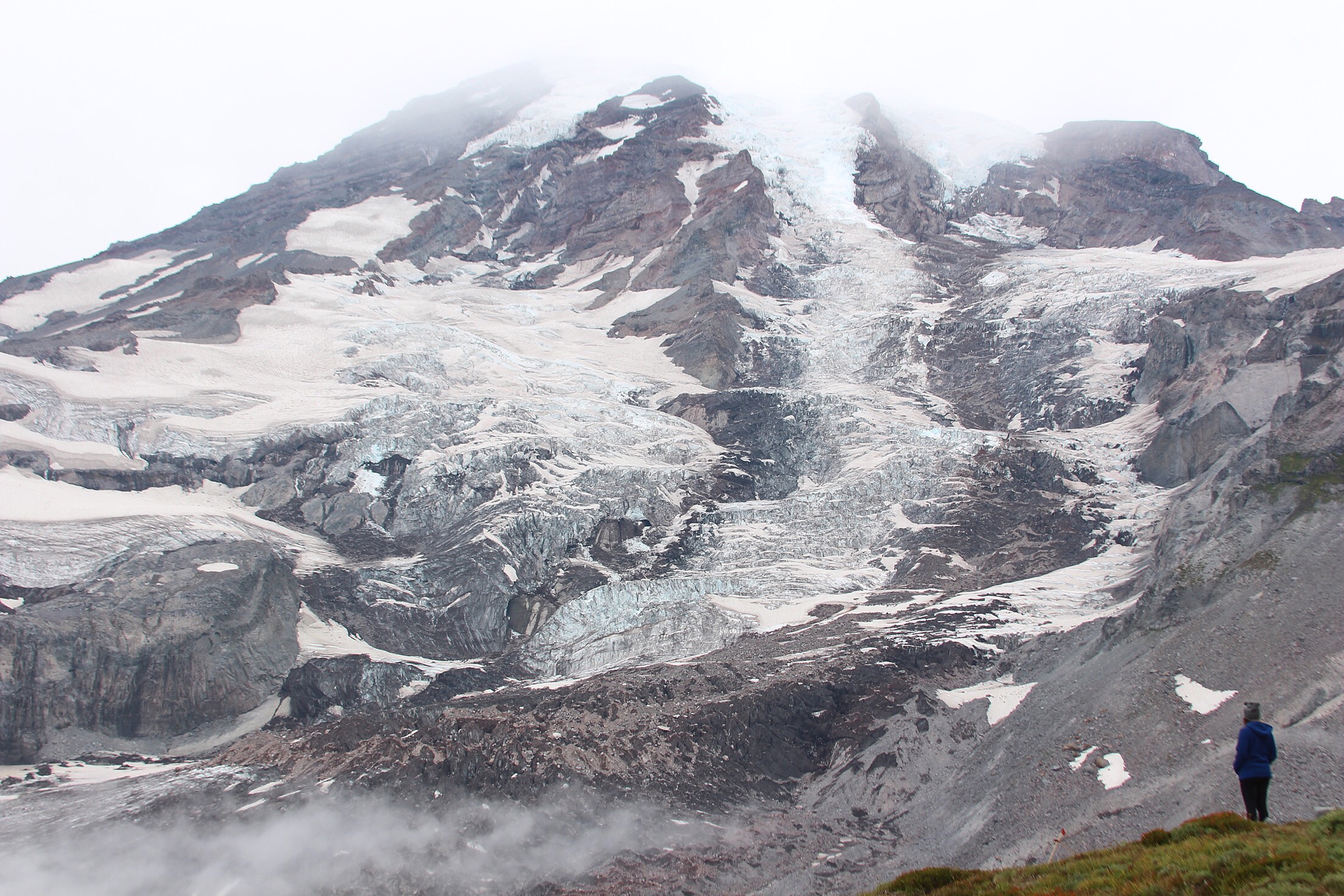

The lasting cost of the alteration, however, beyond Gateway’s $380 million remodeling job (the majority privately funded), falls on the park system as a whole, challenging its values and own identifying rhetoric, like: “Generally, a national park contains a variety of resources and encompasses large land and water areas to help provide adequate protection of the resources.” What’s puzzling then is that there is little inherently natural or expansive about Gateway. The property in total equals 69 football fields, something you could walk in an afternoon. By comparison, Death Valley National Park equals 2,575,758 football fields. The only arguable resource at Gateway is educational and, hence, requires no more protection beyond that of an underground museum and historic courthouse. Other parks protect the tallest, biggest, and oldest trees on the planet; the world’s longest cave system, the country’s clearest and deepest water; the tallest peak in North America; the darkest night skies; the few places that still have true silence; temperate rainforests; ancient bedrock; petrified barrier reefs; the majority of the world’s geothermal features; and all the biodiversity that spans from the Arctic Circle to the Everglades. Yet, Gateway’s trees are planted and ponds artificial. Their website, unlike most other park sites, doesn’t have a nature section in homage to flora and fauna—because at best you might see an opossum. Gateway doesn’t even have naturally growing grass, the gridlines of laid sod guiding your eyes in linear patterns across the landscape. In fact, a ranger told me, after their grand opening on July 3, 2018, the lawn was so spoiled by participants they had to put new sod down—which then spoils, in many ways, the very act establishing the National Park Service as an agency with its famous phrase to leave parks “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

But . . . who really cares? At a time when gun violence is rising, basic human rights are being challenged, and one million species are under threat of extinction in the next few decades, what is the final weight of a squabble over “national memorial” vs. “national park”? The worst that may come of this for most people is having to look at pictures of a steel arch, sandwiched between images of caribou herds and glacial peaks, in upcoming guidebooks. Not emergency status, right? The answer is ambiguous and multifaceted. That’s why I needed to accept the National Park Foundation’s invitation and go see for myself.

—Excerpt from “Steel Reflections”

St. Louis is ancestral lands to the Osage, Miami, Sioux, and Haudenosauneega Tribes.

Related Articles:

Best National Park Road Trips